Beyond the Balance Sheet: Tangible vs. Intangible Assets – Unlocking True Value in the Modern Economy

Greetings, fellow visionaries and stewards of value! As a world-class expert in the realm of 'Assets', I’m thrilled to embark on a journey with you through the intricate landscape of what truly constitutes wealth and potential in today's dynamic world. The term "asset" often conjures images of machinery, buildings, or vast sums of cash. Yet, a closer inspection reveals a far more nuanced reality, one where the unseen often outweighs the seen in significance. To truly comprehend the bedrock of enterprise and investment, we must move beyond simplistic definitions and delve into the fundamental distinctions that shape our economic future.

Today, we're dissecting the core of asset classification through a compelling comparison: Tangible vs. Intangible Assets. This isn't just an academic exercise; it's a critical lens through which businesses are valued, strategies are forged, and competitive advantages are won or lost. Understanding their unique characteristics, how they generate value, and how they interact is paramount for anyone serious about navigating the complexities of modern commerce.

The Foundation: What Exactly Are Assets?

At its most fundamental level, an asset is an economic resource owned or controlled by an entity (an individual, company, or government) that is expected to provide a future economic benefit. These benefits can manifest in various forms: generating revenue, reducing expenses, or contributing to the entity's overall operational capacity. Assets are the building blocks of wealth, the tools of production, and the very essence of economic potential. Without them, no enterprise can truly function or grow.

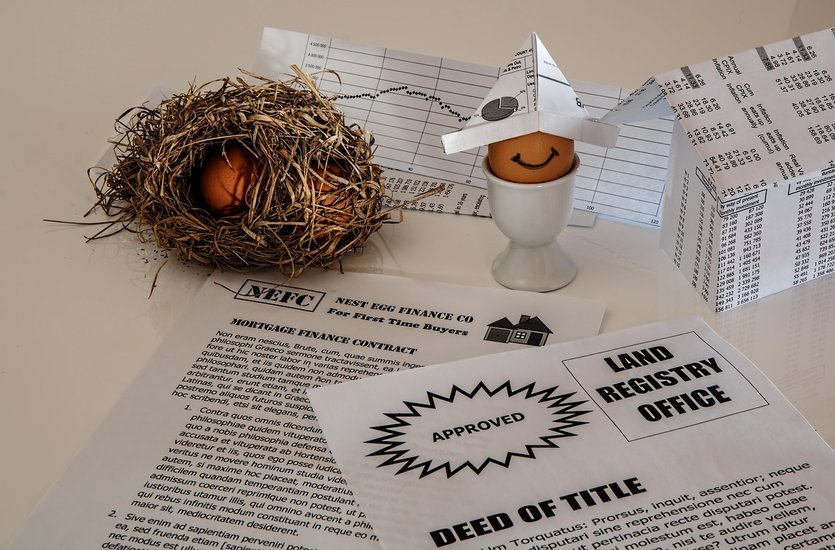

Tangible Assets: The Solid Ground of Value

Let's begin with what most readily comes to mind: tangible assets. As their name suggests, these are assets that possess a physical form, meaning they can be seen, touched, and often physically moved. They are the concrete components of an organization's operational framework, essential for production, administration, and distribution.

Common examples include:

- Property, Plant, and Equipment (PP&E): Land, buildings, machinery, vehicles, office furniture. These are the workhorses of industry.

- Inventory: Raw materials, work-in-progress, and finished goods awaiting sale.

- Cash and Cash Equivalents: The most liquid of tangible assets, readily available for transactions.

- Accounts Receivable: Money owed to the company by customers for goods or services already delivered.

The defining characteristics of tangible assets make them relatively straightforward to identify and often to value. Their physical presence allows for conventional depreciation methods (allocating their cost over their useful life), and they can typically be collateralized for loans or liquidated in a marketplace. Historically, tangible assets formed the vast majority of a company's balance sheet, representing its productive capacity and often its market value. They are the visible manifestation of investment and operational capability, providing a sense of stability and often a clear path to generating revenue.

Key Takeaway: Tangible Assets

Tangible assets are physical, measurable resources that underpin an organization's operations. They are relatively easy to value, depreciate over time, and provide direct operational benefits. Think of them as the visible infrastructure of value creation.

Intangible Assets: The Invisible Engine of Growth

Now, let's turn our attention to the less obvious, yet increasingly potent, category: intangible assets. These are assets that lack a physical form but still possess significant economic value and are expected to provide future benefits. In today’s knowledge-driven economy, these unseen forces often drive the lion's share of a company's competitive advantage and market capitalization.

Examples of intangible assets are diverse and continually evolving:

- Intellectual Property (IP): Patents, copyrights, trademarks, trade secrets, industrial designs. These protect innovative ideas and creative works.

- Brands and Brand Recognition: The reputation, image, and customer loyalty associated with a product or company. Think of the emotional connection and trust a strong brand evokes.

- Software and Technology: Proprietary algorithms, operating systems, applications, and specialized databases.

- Goodwill: Acquired through mergers and acquisitions, representing the premium paid over the fair value of identifiable net assets, often due to strong customer relations, a solid reputation, or synergistic benefits.

- Customer Relationships: The value derived from loyal customers and established client networks.

- Human Capital: The skills, knowledge, experience, and motivation of an organization's workforce (though not typically recognized on a balance sheet in accounting, it's undeniably an economic asset).

- Organizational Capital: Processes, culture, and operational efficiencies.

Valuing intangible assets is inherently more complex than valuing their tangible counterparts. Their value often lies in their potential for future earnings, their exclusivity, or their ability to create barriers to entry for competitors. Instead of depreciation, many intangibles are subject to amortization over their legal or economic useful life. While harder to quantify, their strategic importance cannot be overstated. They are the differentiators, the innovators, and the engines of sustainable growth in the 21st century.

Key Insight: Intangible Assets

Intangible assets are non-physical resources that drive competitive advantage and future economic benefits. They are challenging to value but are increasingly critical for differentiation, innovation, and long-term business success.

The Great Divide: Tangible vs. Intangible Assets

Now that we’ve explored each category individually, let’s formalize their differences. While both are vital for a company's health and prosperity, their distinct characteristics demand different management approaches, valuation techniques, and strategic considerations.

The core distinctions lie in their nature, how they generate value, and their implications for business strategy:

- Physicality: This is the most obvious difference. Tangible assets have a physical presence; intangible assets do not. This impacts everything from insurance to collateralization.

- Valuation: Tangible assets often have clear market prices or can be valued based on replacement cost or historical cost, making them easier to assess. Intangible assets, particularly those unique to a company (like a strong brand or proprietary technology), require more sophisticated and often subjective valuation methods, focusing on future cash flows or relief from royalty.

- Depreciation vs. Amortization: Tangible assets typically depreciate (lose value) over time due to wear and tear or obsolescence. Intangible assets are amortized, expensing their cost over their estimated useful or legal life.

- Risk and Return: Tangible assets can offer a steady, predictable return but might have lower growth potential. Intangible assets often carry higher potential for exponential growth and competitive advantage but can also be more volatile and harder to protect (e.g., brand reputation can be damaged quickly).

- Scalability: Many intangible assets are highly scalable. A piece of software or a strong brand can be replicated or leveraged across a vast market without significant additional physical investment. Tangible assets, by contrast, often require proportional investment for increased scale.

- Strategic Impact: While tangible assets provide the operational backbone, intangible assets increasingly define a company's unique selling proposition, its capacity for innovation, and its long-term market differentiation.

Here's a simplified comparison:

| Feature | Tangible Assets | Intangible Assets |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Form | Yes (e.g., land, machinery) | No (e.g., patents, brands) |

| Valuation | Easier; market prices, cost basis | Complex; future cash flows, strategic value |

| Expense Recognition | Depreciation | Amortization |

| Liquidity/Collateral | Often good; can be sold/mortgaged | Limited; market often illiquid, harder to pledge |

| Role in Value Creation | Direct operational capacity, physical production | Competitive advantage, innovation, brand equity |

The Evolving Landscape: Why Intangibles Are King in the Modern Economy

For centuries, economic power was largely measured by control over tangible assets – land, factories, natural resources. However, the dawn of the information age, the digital revolution, and the rise of service-based economies have fundamentally shifted this paradigm. Today, the companies with the highest market capitalizations are often those whose value is overwhelmingly derived from intangible assets.

Consider technology giants, pharmaceutical companies, or luxury brands. Their immense market values far exceed the sum of their physical property. This "invisible wealth" represents their patents, proprietary software, cutting-edge research, brand loyalty, and the collective expertise of their workforce. These assets are often non-rivalrous (their use by one entity does not preclude use by another) and non-excludable (difficult to prevent others from using them without legal protection), making their protection and leverage critical for sustaining competitive advantage.

The ability to innovate, to build trust, to create compelling digital experiences, and to cultivate unique intellectual property has become the ultimate determinant of success. Investing in R&D, brand building, talent development, and robust cybersecurity are now as crucial, if not more so, than investing in new machinery or physical infrastructure.

Expert Tip: Nurturing Intangible Assets

To maximize the value of intangible assets, focus on robust IP protection, continuous innovation (R&D), strong brand management and marketing, fostering a culture of learning and development (human capital), and building durable customer relationships. These investments, though harder to measure instantly, yield profound long-term returns.

Navigating the Asset Mix: A Strategic Imperative

For businesses and investors alike, a sophisticated understanding of both tangible and intangible assets is not merely beneficial; it's essential for sound decision-making. Strategic leaders must not only optimize their physical operations but also skillfully cultivate, protect, and monetize their non-physical capital. This requires a shift in perspective, moving beyond traditional accounting metrics to embrace more holistic valuation frameworks that recognize the profound impact of intangibles on market value and future potential.

A well-balanced asset portfolio often includes a mix of both. Tangible assets provide stability, a physical base for operations, and often serve as a tangible measure of past investment. Intangible assets, on the other hand, are the fuel for innovation, differentiation, and future growth, offering scalability and unique competitive advantages. The optimal mix varies by industry, business model, and strategic objectives, but the trend clearly points towards a growing reliance on, and value derived from, the intangible.

In conclusion, the world of assets is far richer and more complex than initially meets the eye. By distinguishing between tangible and intangible assets, we gain a deeper appreciation for the diverse ways value is created, sustained, and amplified in the modern economy. For any organization aiming for sustained success, embracing this dual perspective – understanding the visible ground upon which we stand, while simultaneously cultivating the invisible forces that propel us forward – is not just a strategic advantage; it is the fundamental path to unlocking true, enduring value.

Deja una respuesta